Uploaded by

bengunar

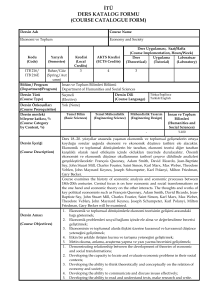

Social Exclusion: Poverty and Participation Essay

Bengünur Bozoğlu, 2073872 Problem of Social Exclusion Social justice (or the absence of social justice) is one of the most significant problems of the humanity in the neoliberal world order. In the Keynesian era, there was an endeavor by the state to bring justice to the society. However, within the new paradigm, neoliberals have introduced a new definition of the concept of “social justice” which reversed the former meaning of it (Brodie, 2018). Now, the state is not responsible for protecting the citizens from the uncertainties of the market, but it is just to facilitate and create market in such a way that most deserving ones get their rewards i.e., who making greater contribution takes the bigger piece of the cake as stated in the Brodie’s article (2018). Similarly, Eizaguirre et al. (2012) argues that in the neoliberal order, the notion of “social citizenship” is substituted by the notion of “social cohesion”. This substitution points out to eradication of social justice objectives of the nation state in its redistribution policies in the welfare times. However, in the Brodie’s study, the argument goes, social welfare policies are unjust because they spoil the symbiotic relationship between reward and contribution. In such a competitive environment, neoliberalism loads full responsibility to the individuals and undertakes a blaming role regarding them for their failures in the market although the fact that people are not that powerful to change the rules of the game on their own, according to Brodie (2018). So, in this neoliberal atmosphere, inequality appears as an inevitable outcome. Likewise, Brodie argues that “inequality, whether measured in terms of income, wealth, well-being, or life opportunities, has been the defining legacy of neoliberal market affirming discourses, policies and practices” (2018, p.18). From this point forth, “social exclusion”, which can be seen as a consequence of social 1 inequalities in the society, will be discussed in this paper as another major issue for humanity. This concept will be tackled with a reference to two main issues: poverty and participation. Firstly, we should frame the concept of “social exclusion”. According to Arriagada, social exclusion can be explained with its two dimensions: “lack of social ties linking the individual with the family, community and, more generally speaking, society, and lack of the basic rights of citizenship” in general (2005, p.104). Besides, Reimer emphasizes Room (1995) and Chapman (1998)’s ideas that “social exclusion and inclusion is about having access and resources critical to well-being” (as cited in Reimer, 2004, p.77). He argues that people can gain access to them in various ways. In this regard, he defines four types of social relations in the society in which exclusion might occur. These are market, bureaucratic, associative and communal relationships. According to him, people can gain access to resources and services by using these types of social relations. However, in order to do so, they should meet the norms of the dominant types of relations. Failure might mean exclusion from any or all types of relationships and resources and services provided by them. For example, one need to be capable of adapting formal structures and procedures in order to benefit from bureaucratic relations. That is to say, people who form more personalized relations may be excluded from this formal structure. To illustrate, a family might not be able to access the government’s transfer payments. Additionally, one has to have access to tradable goods and services, enough information about markets and prices or negotiation skills, for example, in order to take action in the market relations. Failures to do so, again, might mean exclusion from the market. After putting the general framework for the “social exclusion”, a concept in relation to it comes to the front, which is “poverty”. Focusing on the examples presented above, it is clear that exclusion in different degrees from these types 2 3 of relationships brings about poverty. For example, if one cannot participate in labor the market, it is obvious that he cannot earn income within that relationship. Similarly, he cannot compensate for this situation with the help of government subsidies, for instance, if he is also excluded from the bureaucratic type of relationship. Moreover, according to Mitlin (2005), connections are important for accessing basic services and livelihood opportunities. In parallel to this, informal ties may help reducing poverty. Patronage relations, for example, may ease the process of seeking for work. On the contrary, poor connections may mean low level of job opportunities. Similarly, discrimination -which is a type of social exclusion- in labor market and residential settlements might bring about poverty, as Mitlin argues (2005). For instance, being a woman, being old or belonging to an ethnic group may make difficult to secure livelihood In short, once people are socially excluded, it is much likely that they fall into poverty. With an imagination we can say that one of the most important ways of earning money is participating in the market relations. There are other ways of making money, of course. However, if one is being excluded from communal relationships or bureaucratic relationships for example, the only place to gain money becomes the market. Mitlin (2005) argues that, even if one can participate in the market relation, he might still be in poverty because of low wages, informal markets, demand for specific skills, job insecurities, or poor working conditions. As an addition, low income profoundly affects the living standards by reducing the chance of getting proper education. Thus, the possibility to get into market in the future falls as well, which causes the emerging of vicious circle that makes poverty a hard problem to be solved individually. At this point, as one of the most important components of social exclusion, we should explain what poverty is. According to Arriagada, poverty means “the deprivation of essential assets and opportunities to which all human beings are entitled”. Also, she states that “poverty is related 4 to unequal and limited access to productive resources and to a low level of participation in social and political institutions” (2005, p.100). Moreover, she puts a number of elements for a proper definition of it like income level, access to goods and services provided by the government, difficulties in getting educated and limited free time for it together with resting and recreative activities. Besides poverty, the concept of “chronic poverty” points out to severity and multidimensionality of poverty. As Mitlin (2005) states, it is basically the duration that differentiates chronic poverty from poverty. However, because of its multidimensional character, assessments about it should also be multidimensional. That is to say, for both Mitlin (2005) and Arriagada (2005), using only money-metric measurements is not appropriate to assess it. Especially regarding the spatial analyses of him, Mitlin (2005) argues that one should take into account features like price levels across different spaces, expenditure habits, level of commodification or the existence of non-food essentials in some areas etc. Arriagada (2005) also mentions the fact that causes and characteristics of it change on a special basis. We should not forget that besides the place of residence, vulnerability also matters to define poverty appropriately (Mitlin, 2005). Similarly, Arriagada (2005) states that in order to interpret the exact nature of poverty, we should also look at cultural factors such as gender, race, ethnicity and economic, social and historical context. All in all, once again focusing on the conceptualization of poverty, it is clear that it is an important reflection of social exclusion. There is a reinforcing relationship between the two. That is to say, social exclusion can cause poverty on the one hand, and poverty can reinforce social exclusion on the other. The second critical point to be addressed in this paper in relation to social exclusion is the issue of participation. As it is known, participation constitutes one of the most important cornerstones in the neoliberal agenda, especially when the emergence of the governance paradigm 5 is considered. This notion started to be supported by the policies of international organizations. For instance, in the European Commission’s White Paper on governance, the virtues of democratic governance were promoted such as transparency, accountability, participation and effectiveness (Eizaguirre et al., 2012). With this emphasis, multileveled decision-making processes, cooperation between market and civil society in multiple policy-making scales, a competitive environment have come to the front, as stated by Eizaguirre et al. (2012) with the EU’s regulatory role especially. It should be noted that in this competitive environment in which economic growth is seen as more important than economic redistribution, social inequalities has increased. In this frame, European Commission has drawn attention to the increase in poverty and social exclusion and recognized the need to implement social inclusion policies (Eizaguirre et al., 2012). Thus, we see an increasing effort to diversify the participation methods, to go beyond voting behavior which is only a one dimension of participation, as an inclusion mechanism, but it is debatable (Wilson, 1999). Regarding the participation issue, two main discussions should be made in the framework of social exclusion. The first one is that more participation does not necessarily bring about more democracy as Wilson stated (1999). That is to say, more participation does not mean that the demands of participants will be heard and taken into consideration, as it should be in democracies. According to him, effectiveness and activity do not mean the same. In other words, although there are lots of initiatives for enhancing participation, policy impact for some specific sectors in the society may not be at the sufficient level or simply does not exist. Even, these initiatives may increase the expectations that cannot be met. So, this makes socially excluded groups who participate for the first time feel disenchantment (Wilson, 1999). To give an example, last week in the commission, the minimum wage was announced in Turkey. In the decision-making process, the state, representator of employers and representator of employees were all included. However, 6 the representation of the employee stated that they were against the decision. This clearly states that participation does not necessarily lead to policy impact. In this point, the issue of social exclusion gains importance regarding the participation debate. Wilson states that “patterns of social exclusion can be reproduced within participation initiatives” (1999, p.252). To continue the example above, even if employees participate in the decision-making process, the fact that their demands are constantly undermined makes the hierarchy between the stakeholders more obvious. We should not ignore the fact that there are power asymmetries in the table of decision-making. Some groups or individuals may dominate the process because of their privileged position due to economic reasons, for instance. Also, human resource opportunities may create inequalities between the participating groups due to education level or know-how, for example. Wilson also comes to the conclusion that initiatives to increase participation actually doesn’t change the power relationships but “reinforces existing patterns of social exclusion and disadvantage” (1999, p.252). The second pillar of the discussion is that there might be some participation barriers, especially for the socially excluded people. First, according to Evans “effective political participation is linked to educational attainment, political equality and, most significantly, economic resources and political efficiency” (as cited in Wilson, 1999, p.258). Second, there should be time and energy for one to participate in decision-making processes of public policies. However, poor people might see direct participation as a “risky and time-consuming strategy” (Hickey and Bracking, 2005) Apart from this, they argue that the poorest mostly prefer to delegate their participation rights to intermediaries since they tend to avoid from directly participating (2005). At that point, the issue of representation should be touched upon. According to Hickey and Bracking (2005), the representation of the poor can be realized with two channels. One is discursive and the other is material way. He argues that in a discursive manner the poor are spoken “of” in 7 academic and policy discourses. He continues his argument by stating that four formal or informal actors from civil or political life can speak “for” the poorest: civil society organizations, political parties, political elites and informal political actors. However, in each type of representation there might be problems. For example, there may occur misrepresentation problems in the civil society organizations, or even the groups consisting of poor people may exclude the poorest ones. Regarding political parties, there is the possibility that even the pro-poor parties may fail in terms of adequate representation. Also, since the poor does not constitute a constituency as a whole, the poorest again may not be represented because of “politics of middle-ness”. Regarding the political elites, the differences between the local and national elites may point out a problem. Lastly, the representation of the poor within the patron-client relationships might be reproducing the local causes of poverty. All in all, if we approach to the issue of participation and representation especially considering the poverty, we can say that as Hickey and Bracking argue in poverty assessments, the inclusion of the poor weight less than the ways in which they are represented within the elite political discourse (2005). One critical point to address here is that when these problems of representation are taken into consideration, the effectiveness of it becomes debatable. Of course, self-representation is better than representation with one of the agents above. However, as I mentioned earlier, the poor people for example, do not have a chance to actively or effectively participate in the processes. Here it seems that there is a paradox. Neoliberal agenda wants the poor to participate in decision-making activity at least in order to provide a peaceful atmosphere for reproduction of the system on the one hand. This was mentioned above, especially in the context of decreasing social inequalities and exclusion and enhancing social cohesion. However, on the other hand, we see that this is not possible, in an ideal manner. Here, we should look at the ideas of Marx and Rousseau, as cited in Bracking’s article, for the majority of the poor, the ideals in the 8 liberal ideology cannot be delivered in the capitalist societies. This is because the equal opportunity for participating and attaining comprehensive well-being and precious existence are undermined desperately by the economic conditions of liberalism itself. This is just an illusion. Yet, at this point, quoting Bracking would be meaningful: “liberal representation is better than no representation, but it is not adequate representation” (p. 1022, 2005). To sum up, in this paper, the issue of social exclusion was discussed in relation to two concepts which are poverty and participation. In short, neoliberal world order is obviously full of inequalities. Unsurprisingly, constant reproduction of these inequalities makes the problem of poverty tangled. In this paper, poverty was explained with its relation to social exclusion, and it is argued that social exclusion and poverty may reinforce each other. Second, the representation and political participation of the socially excluded people was mentioned. It was argued that, although neoliberal discourse seems to glorify participation, when it comes to the socially excluded groups, it just turns to an illusion. This can be best understood with the absence of policy impact. 9 REFERENCES - Arriagada, I. (2005) “Dimensions of poverty and gender policies”, Cepal Review 85 (April 2005): 99-110. - Bracking, S. (2005) “Guided Miscreants: Liberalism, Myopias, and the Politics of Representation”, World Development 33(6): 1011–1024. - Brodie, J. (2018) “Inequalities and Social Justice in Crisis Times”. In J. Brodie (ed.) Contemporary Inequalities and Social Justice in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press: 3- 25. - Eizaguirre, S. et al (2012) “Multilevel Governance and Social Cohesion: Bringing Back Conflict in Citizenship Practices”, Urban Studies 49(9): 1999–2016. - Hickey, S. and S. Bracking (2005) “Exploring the Politics of Chronic Poverty: From Representation to a Politics of Justice?”, World Development 33(6): 851–865. - Mitlin, D. (2005) “Understanding Chronic Poverty in Urban Areas”, International Planning Studies 10(1): 3–19. - Reimer, B. (2004) “Social Exclusion in a Comparative Context”, Sociologia Ruralis 44: 76–94. - Wilson, D. (1999) “Exploring the Limits of Public Participation in Local Government”, Parliamentary Affairs 52 (2): 246-259. 10